Central Hall (Room 100)

[Existing physical evidence includes the plain plaster cornice and entablature, with plaster rosettes applied at regular intervals on the entablature. The wainscoting on the lower portion of the walls is a later application and matches that in room 104; the wainscoting was not present during the target date 1857-1862. The scenic wall covering above the wainscoting was added in the 1960s following the City’s acquisition of Verandah House and is inappropriate for the target date. The oak parquet floor was laid over the original 6-inch-wide pine floor sometime in the 2nd quarter of the 20th century by the Curlee family. The original wide board pine floor remains in place.]

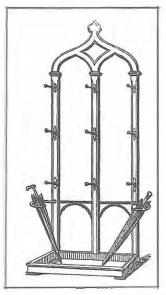

This hall tree in a simple Gothic style was illustrated by Andrew Jackson Downing who identified it as a “hat and cloak stand.” As shown, it also held umbrellas. Only men would leave their hats on the stand as women guests wore their hats while visiting. (Andrew Jackson Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), p. 441)

There is no question that this commodious hall measuring 12 x 35 feet served the Mask family as a living room as well as a passage way. As far north as Philadelphia, families used similar central passages with doors at either end as cool and breezy retreats from summer heat. Sketches show families dining, reading, sewing, and generally socializing in their halls as well as on their verandahs. The Verandah House collection has several objects appropriate for such use including a Federal flip-top card table with tapered square legs and a mahogany Grecian flip-top card table with urn support and scrolled feet. A set of four chairs comprising one arm chair and three side chairs, mahogany, in the late Georgian style with upholstered seats could be placed along the north side of the hall and finished with matching slip-covered seats appropriate for summer use which is when the house is open for tours. This set of chairs would replace the gilt sofa and two chairs in the Louis XIV style which are inappropriate for the target date and should be de-accessioned. A hall tree of appropriate date and placing it near the front door.

Rather grand halls, such as the one in Verandah House, might be used for socializing all year including musicales and dancing. The piano mentioned in the 1857 tax assessment might well have been in this space although the “box” piano currently on the south side of the hall date to 1884 and should be replaced with something earlier and smaller. In the meantime, the Grecian sofa with the pink taffeta upholstery should be slip covered to match the set of chairs and placed on the south wall along with the tilt-top tripod table and the oil painting, “Boy on a Couch.

The 1857 tax assessment also included a clock at $8.00, which was the highest valuation on the list. This value suggests it was a tall-case clock which certainly would have stood in the center hall; the Commission should consider acquiring one for the property and installing it at the west end of the hall to the left of the door.

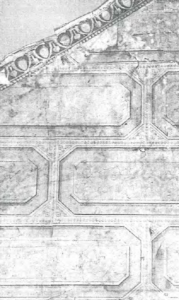

A fragment of ashlar wallpaper complete with an acanthus border from the stair hall of a town house, dating 1845-1860. Colors match recommendations of A. J. Downing for hallways. (Catherine Lynn, Wallpaper in America (1980), pp 288-289)

It is likely the soft-cast plaster walls were papered soon after the family moved into the house. The wainscoting, which is not original, should be removed and the walls papered from baseboard to cornice with a paper resembling ashlar (quarry-cut) blocks of stone topped with a wallpaper border just below the cornice. As for the wall color, Andrew Jackson Downing (Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses, p. 403) recommends the hall “should be of a cool and sober tone of color–gray, stone color, or drab…and simple in decoration [so that] the richer and livelier hues of the other apartments will then be enhanced by the color of the hall….”

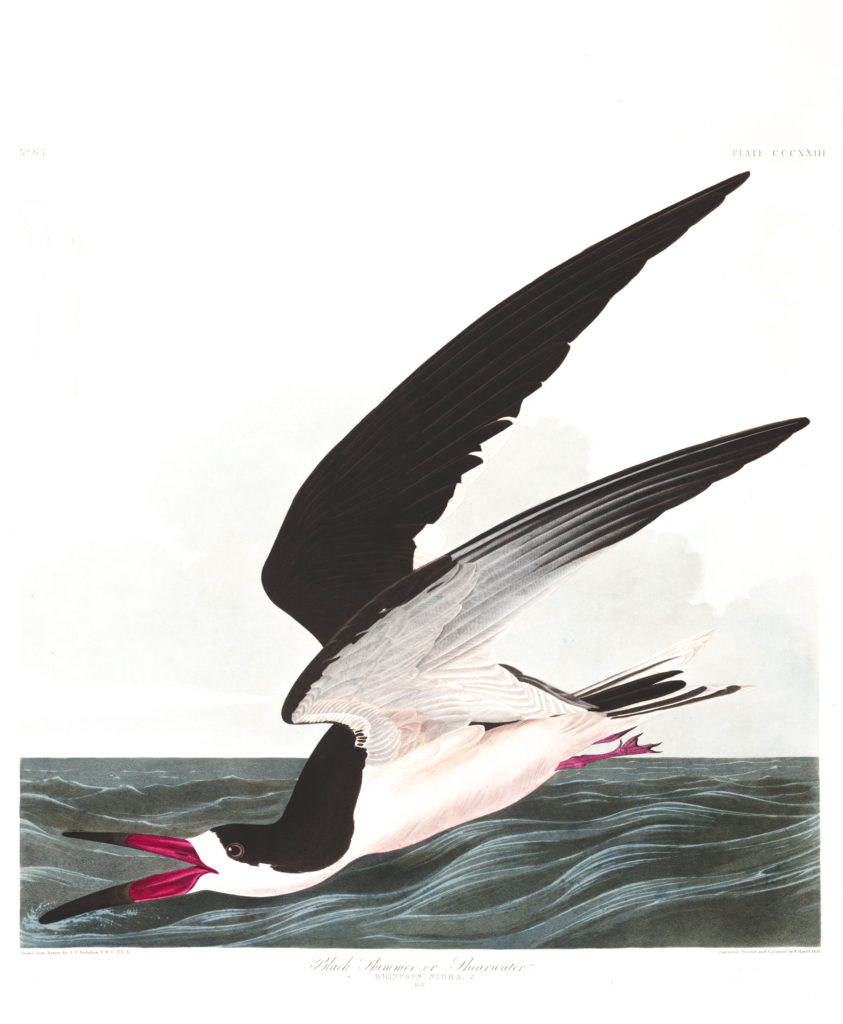

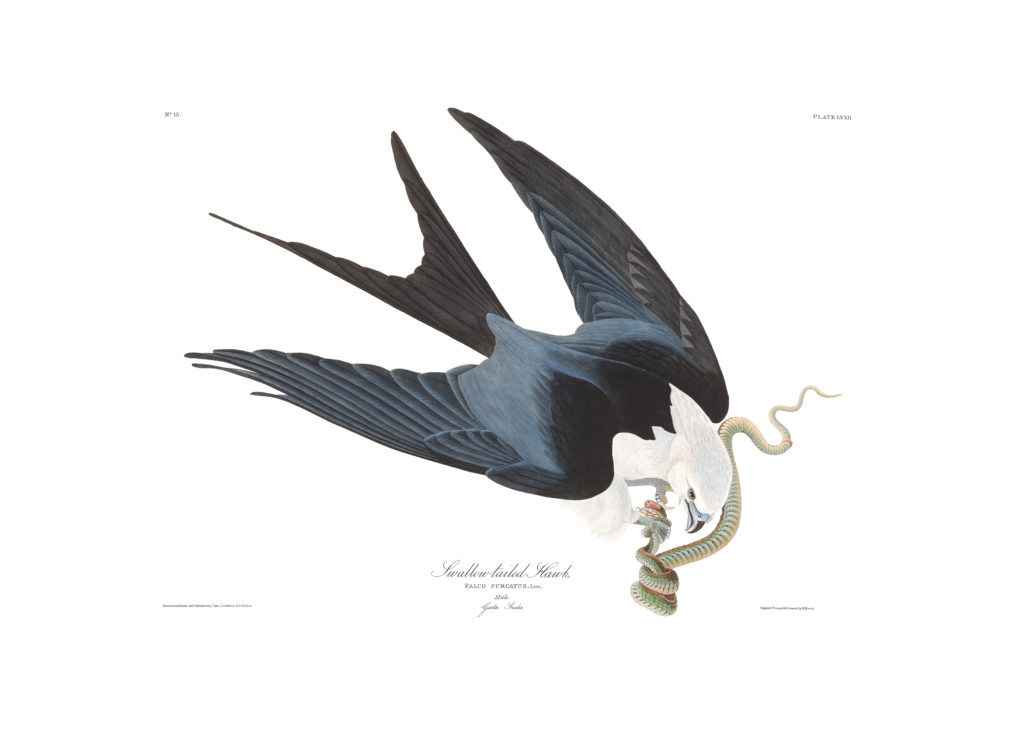

The collection of the Verandah House is fortunate to include several bird and animal prints by John James Audubon (1778-1851), printed by Robert Havell, Jr. (London,1827-1838) and Julius Bien (New York, 1858-1860). These prints have previously been displayed in various rooms, but the historic furnishings plan recommends this small but valuable collection of bird prints be brought together and hung in the hall using security locks available from dealers in museum supplies. The framed prints include ‘Black Skimmer,” “Swallow-tail Hawk,” “Brown Thrushes and Snake,” “White-fronted Goose,” “Yellow Crowned Heron,” “Red-tailed Hawk, Male and Female with Hare,” and “Dusky Duck.” The pictures below are linked to the artist’s notes on the National Audubon Society website.

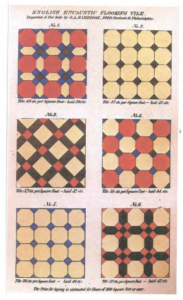

The floor in the hall should be covered wall-to-wall with a painted floor cloth. Downing preferred encaustic tile floors, which were produced in English potteries and had begun being imported to the United States at mid-century, noting they were far more durable than floor cloths. While he was unquestionably correct, there is no evidence for encaustic tiles in Verandah House and having a floor cloth painted to reproduce a mid 19th-century tile pattern in original tile colors (terra cotta, buff, blue, chocolate brown, ivory, etc.) would be appropriate and, as Downing inadvertently informs us, would follow the common practice at the time.

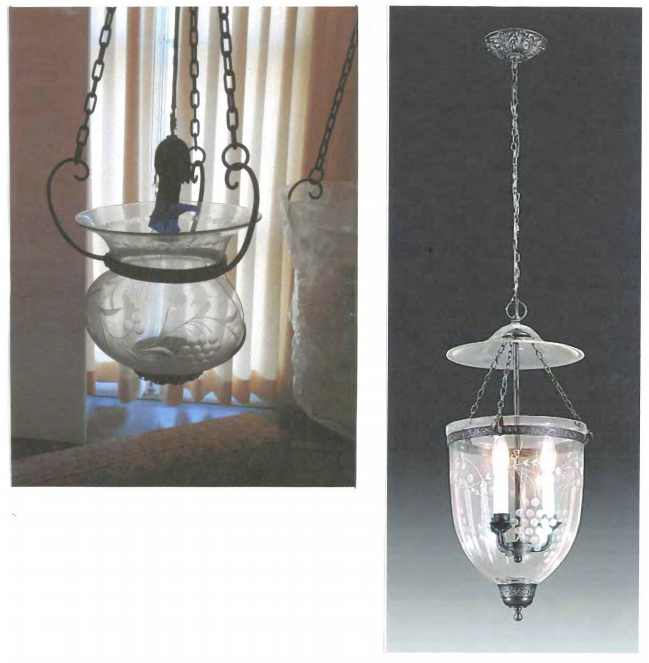

As for lighting, Verandah House possesses two electrified hall lanterns that are the correct basic form for the target date 1857-1860, although they are probably early 20th-century electric reproductions installed by the Curlee family. Each is suspended from a ceiling medallion that is also correct for the house. Both fixtures require work, however. The metal arms, bands, etc. need conservation and the glass bowl of one has a large piece broken out that might be repaired using glass adhesive. Both fixtures need the internal lighting component replaced with more realistic “candles,” and both fixtures should be outfitted with smoke bells which may/may not remain in the collection. Depending on the cost of this restoration work, it might be simpler and less expensive to acquire modern reproductions currently on the market.

Finally, regardless of the hall lanterns used, all ceiling fixtures should be installed so the bottom is no higher than 6 ½ to 7 feet above the floor for the practical reason that the original lanterns, like all other hanging fixtures in the 1850s, would burn candles or lard oil and would need to be easily accessible to light them as well as clean and service them.